The Revival of Liberica Coffee in Malaysia

Article commissioned for crema magazine. This version has been translated.

“The plant that grows on clay, the plant that grows like a fence, sacrifice tree – I’ve heard countless descriptions over the past 17 years,” says Dr. Steffen Schwarz, who has been researching the rare coffee species Liberica for nearly two decades. From his own experience, he knows that myriads of names have taken root among coffee farming communities around the equator. Hardly anyone used the official name Liberica, which significantly hampered his research. “When I first started delving into the subject, the most helpful resources were old books from around 1880,” the coffee expert recalls. “I kept pressing traders for information, but all I got was that the coffee tasted bad and was difficult to cultivate. Nothing more. I wanted to know precisely why the mathematically third-largest species had almost completely vanished from the coffee market.”

To this day, of the four commercially cultivated coffee species, most coffee drinkers are only familiar with Arabica and Canephora, colloquially known as Robusta. Liberica and its cousin Excelsa grow quietly in their shadow – outgrowing them, at least in terms of plant size. Liberica trees are giants that can reach a formidable height of 15 meters. The rare species originated in West African Liberia, which explains its name. Today, it’s primarily cultivated in Southeast Asian countries like Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines. In global coffee trade, Liberica holds minimal presence with less than one percent market share. Yet this resilient plant offers answers to many existential challenges caused by climate change that give coffee farmers worldwide sleepless nights – but more on that later.

His thirst for knowledge was further fueled by travels to various coffee-growing countries. In India and Mexico, for instance, Dr. Schwarz discovered Liberica trees growing like hedges around the perimeter of coffee plantations, infested with pests, functioning like pheromone traps. “The striking size of the leaves and coffee cherries was so distinctive that suddenly I spotted Liberica trees everywhere.” Botanical detective work was required. The coffee scientist kept gathering clues that fit together like puzzle pieces, gradually revealing the secrets of the Liberica plant. “Liberica has less caffeine than Canephora and roughly the same as Arabica. Some of the approximately 30 Liberica varieties I’m familiar with have even less caffeine than Arabica. The sugar content, by contrast, can be up to twenty times higher,” Dr. Schwarz notes.

When he first tasted Liberica coffee, Dr. Schwarz was completely taken by its sweetness. “When Liberica is processed correctly, it holds tremendous potential. Due to its high sugar content, however, it begins fermenting immediately after picking, so it must be processed within 30 minutes at the latest. If this doesn’t happen, the result is a confusing flavor profile marked by earthy, leathery notes and lactic acid,” Dr. Schwarz explains. This at least partially explains why literature claims Liberica tastes terrible. In search of the whole truth, Dr. Schwarz tracked down a Brit who was repeatedly cited as the original source of this flavor misjudgment. “When I met him in London, it turned out he had only picked it up somewhere himself and had never actually tasted Liberica.” Today he knows that with the right methods, Liberica coffee yields a fruit-heavy, tropical cocktail that can burst with mango, papaya, jackfruit, or durian.

To save the species from extinction, Dr. Schwarz encourages coffee farmers to defy the challenges of cultivation and expand their Liberica stock. On the Malaysian part of Borneo, he found a reliable partner in Dr. Kenny Lee Wee Ting of Earthlings Coffee. With technical support from Dr. Schwarz, the coffeepreneur championed the rediscovery of the Liberica plant in the state of Sarawak. “The first Liberica trees reached Sarawak in the 1870s, when Arabica cultivation across South and Southeast Asia was being ravaged by coffee leaf rust. Attempts were made to replace Arabica with Liberica, but cultivation was abandoned after a short time,” Dr. Kenny explains. We wanted to know more about why Liberica found so little acceptance. “It’s partly because Liberica yields only six to seven kilograms per 100 kilograms of coffee cherries. Arabica and Robusta have a yield rate of 25 percent by comparison. The Liberica coffee bean has low density, while the fruit flesh is very thick and hard. The harvest simply didn’t generate enough profit,” he states.

Nevertheless, Liberica trees continued growing in village front yards and wild in the jungle. Their cherries were collected by locals for personal use and blended with other varieties. “In local coffee culture, Liberica was always present, but due to its poor reputation, the species received little attention in the specialty segment. My interest was only sparked when Dr. Schwarz convinced me at a meeting in Bangkok that Liberica is good coffee,” Dr. Kenny reflects on this pivotal moment. “He insisted the problem wasn’t Liberica, but the wrong approach to cultivation and processing. Today we know he was right. Coffee is not all the same. You cannot treat Liberica like Arabica – neither in production nor at the cupping table,” he concludes.

Discover Beans from Earthlings Coffee

Since that encounter, Dr. Kenny has been fighting alongside coffee farmers in Sarawak for Liberica’s revival. “Currently, demand exceeds supply. We produce between 200 and 300 kilograms of Liberica annually. Since cultivation is very labor-intensive, we have to do considerable persuading with coffee farmers. The height of the trees and the thick skin of the coffee cherries make picking extremely difficult. Low yields coupled with high production costs present major challenges,” says Dr. Kenny. For their progress in Liberica cultivation, Earthlings Coffee was awarded the Kaldi Award of Green Coffee at the 2018 Stuttgart Coffee Summit. A year later, experts from around the world traveled to Sarawak to attend the Liberica Symposium Borneo. The world’s first producer of Specialty Liberica, My Liberica from the Malaysian state of Johor, was among them.

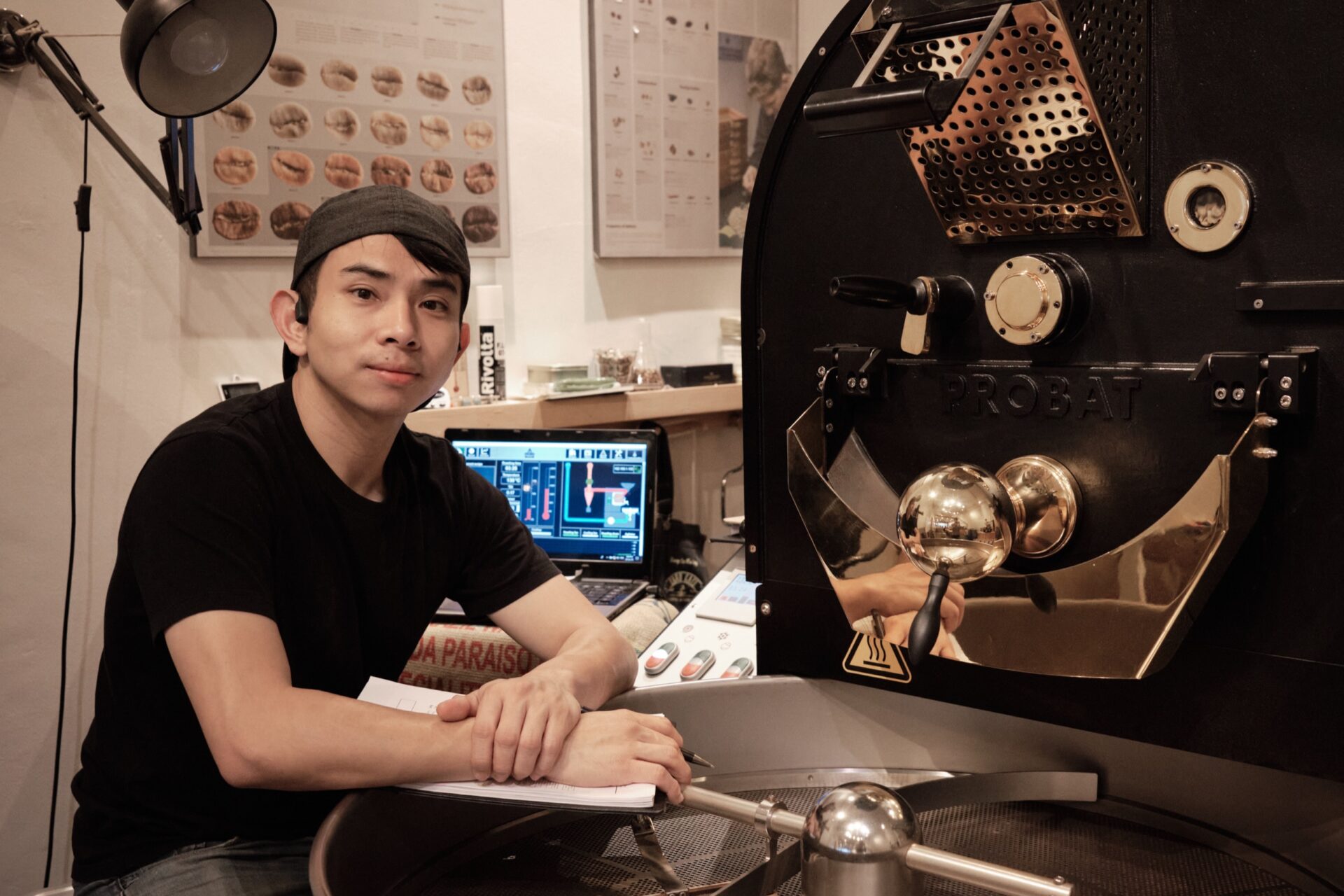

My Liberica, a company that today encompasses a farm, processing facility, and four coffee shops, has its origins in producer and roaster Jason Liew’s passion for coffee. “Twenty years ago, my father first started growing Liberica coffee. Like so many coffee farms, ours is located just a few meters above sea level. Although Malaysia lies along the coffee belt, our soil is largely unsuitable for Arabica cultivation,” Jason explains. The robust Liberica plant thrives at low altitudes – even on clay or peat soils – and adapts well to its environment. This is why it has prevailed in Malaysia, accounting for a remarkable 90 percent of coffee cultivation. Unlike Arabica, Liberica depends on cross-pollination. “On our farm, we have no control over which pollen our Liberica trees receive. In terms of taste, however, this doesn’t have major effects,” Jason adds. “Fermentation plays a bigger role here.”

After founding My Liberica in 2011, Jason began researching how to improve the quality of Liberica – starting with selection and roasting. “We handed our coffee cherries over to traditional coffee processing operations, but they lacked any connection to specialty grade coffee. Production costs were already high, so they weren’t willing to optimize their methods,” he reports. In 2014, My Liberica established their own processing station for coffee cherries. This allowed them to test sun-dried, semi-washed, and washed processing methods tailored specifically to Liberica. “From a cost perspective, semi-washed processing is advantageous. In terms of taste, sun-dried processing is the clear favorite, especially for Liberica’s debut on the specialty market.”

Discover Coffee from My Liberica

Jason has a clear goal in mind: “We want to increase the quality and production of Specialty Liberica and make it profitable through export.” He’s supported in this ambitious endeavor by former World Barista Champion Sasa Sestic. Known for his innovative processing methods, the founder of ONA Coffee introduced Jason to anaerobic fermentation. “We found the sweet spot after 20 days of anaerobic processing. This resulted in intense flavor characteristics in the red fruit range that we had never been able to coax from the beans before,” Jason says proudly. Strawberry cheesecake or ripe banana are aromatic qualities that should undoubtedly appeal to sensory professionals.

These new processing approaches enabled Liberica to make its presence known in previously untouched territory: the World Coffee Championships. My Liberica made it to the world stage twice: in 2021, Hugh Kelly placed third at the World Barista Championship without running a single gram of Arabica through his grinder. For the obligatory milk beverage, he used an espresso blend of 50 percent Eugenioides and 50 percent Liberica. In 2022, Danny Wilson mixed his way to fifth place at the Coffee in Good Spirits Championship with a Liberica signature drink. Despite all the enthusiasm that Liberica is finally receiving the recognition this rare coffee species deserves, a bitter aftertaste remains. “When we ferment Liberica anaerobically to bring it to drinkable maturity for the specialty market, yields drop from seven to just four percent,” Jason laments.

Despite high production costs, low yields, and the considerable effort required for harvesting and processing, Dr. Schwarz, Dr. Kenny, and Jason Liew agree: Liberica coffee has a fruitful future ahead. “With recent changes in world climate, the importance of ecological adaptability of coffee varieties has been recognized,” says Jason. “The adaptive Liberica has a clear advantage here.” According to Dr. Schwarz, Liberica represents a tremendous opportunity and the best answer to climate change: “The root system works differently. It reaches much deeper than any other coffee tree. During drought, the shallow root network of Canephora cannot compete.” Dr. Kenny’s belief in Liberica’s potential is equally unshaken: “Liberica will be on everyone’s lips worldwide. Every coffee farmer will grow Liberica trees in the future.”